4페이지 내용 : 4 KOREA July _ 5 Written by Sammy Seung-Min Lee, artist and board of director, Asian Art Association, Denver Art Museum Cover Story » “Would you say you’re in a romantic relationship with Hanji?” So asked a curator during one studio visit, as she listened to me explain my creative process. “Yes,” I replied, afer some hearty laughter and contemplative refection. “It’s been a wonderful relationship, indeed.” Many artists ofen project themselves into various materials throughout their career, but end up gravitating toward one specifc medium of choice. I am one such artist, and Hanji has become my preferred material over the years. While I fell in love with Hanji at frst for its sof appearance, I stayed in love with the material for its strength and durability. For the past decade, I have been incorporating Hanji and the process of its creation into my work. Its infuence is present throughout my artistic journey across various forms, including artistic books, performances, interactive installations and more. As I’ve now spent the latter half of my life in the United States, I am defnitely Korean-American, and not just Korean. Another one of Hanji’s particularly attractive qualities, however, is its origins and ties to my mother country. Hanji translates literally as “Korean paper,” with han meaning “Korean” and ji signifying “paper.” Like a mother, it is graceful and delicate — sometimes even wrinkled — yet also fexible, resilient and forgiving. Te processhow Hanji is made Hanji is deeply rooted in traditional Korea and is a byproduct of site-specifc resources. Te paper is handmade with bark derived from the paper mulberry, a native tree. Te trees are bountiful in Korea, thriving on the country’s rocky mountainsides. Harvesting mulberry bark and making Hanji has long been a communal pastime during the winter. Mulberry fbers are naturally long but are especially strong when harvested in cooler temperatures. Before agricultural activities got into full swing, villagers would use this slower working period to participate in the laborious process of papermaking. It begins with trimming bark from trees, then steaming it for several hours. Afer that, the material is peeled, cleaned, bleached in the sun and cooked with a plant ash solution. Once the fbers have been pounded and poured into a vat with hibiscus root extract, it is ready at last, transformed into paper. Tis is merely a summary of the papermaking process, however. Preparing these fbers is an ancient process, developed and perfected over the course of thousands of years. It is meticulous and scientifc. Te plant ash, for instance, is an alkaline solution. Cooking the fbers in it is an alchemical transformation, yielding a material that is stable and perfectly, chemically balanced. Te painstaking papermaking process also gives Hanji a particularly strong quality, in contrast to the standard unsubstantial perception of paper. Te single cord–forming method, or oebalddeugi, is a derivation uniquely devised in Korea. Tis approach allows fbers to move freely and overlap. Te fbers ofen crisscross at 90 degree angles as a result, contributing to the paper’s rugged nature. One step also calls for the layering of two wet layers and fusing them together, in order to increase durability. Tis doubling is the inspiration of one of Hanji’s nicknames, “yin-yang paper.” No Lost Art Hanji, traditional Korean paper, continues to inspire Kwon Youngwoo, Untitled, 1980s, Hanji, 100x80.5cm. Courtesy of The Artist’s Estate and Kukje Gallery. Image courtesy of the KukjeGallery

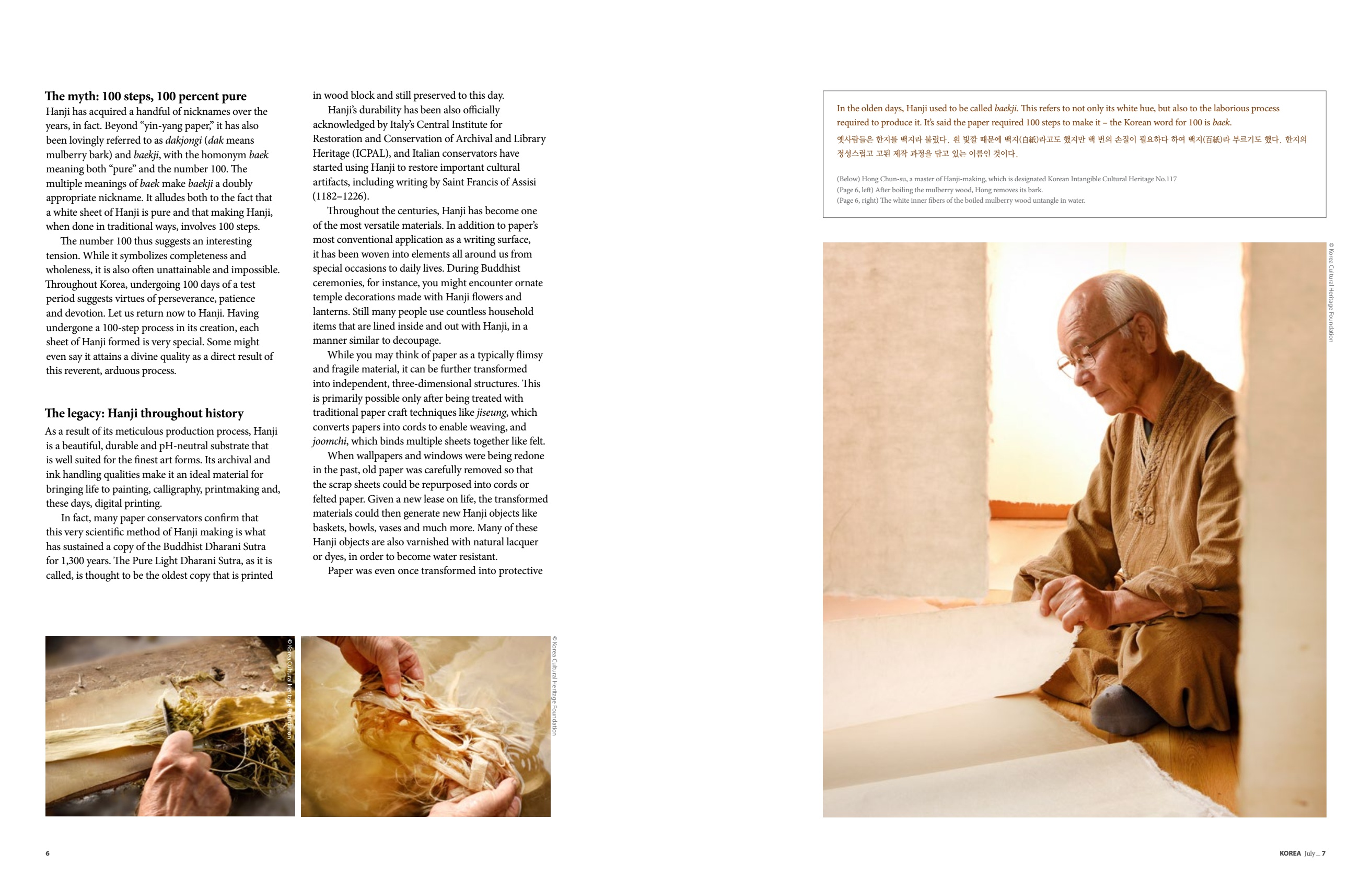

5페이지 내용 : 6 KOREA July _ 7 Te myth100 steps, 100 percent pure Hanji has acquired a handful of nicknames over the years, in fact. Beyond “yin-yang paper,” it has also been lovingly referred to as dakjongi dak means mulberry bark and baekji, with the homonym baek meaning both “pure” and the number 100. Te multiple meanings of baek make baekji a doubly appropriate nickname. It alludes both to the fact that a white sheet of Hanji is pure and that making Hanji, when done in traditional ways, involves 100 steps. Te number 100 thus suggests an interesting tension. While it symbolizes completeness and wholeness, it is also ofen unattainable and impossible. Troughout Korea, undergoing 100 days of a test period suggests virtues of perseverance, patience and devotion. Let us return now to Hanji. Having undergone a 100-step process in its creation, each sheet of Hanji formed is very special. Some might even say it attains a divine quality as a direct result of this reverent, arduous process. Te legacyHanji throughout history As a result of its meticulous production process, Hanji is a beautiful, durable and pH-neutral substrate that is well suited for the fnest art forms. Its archival and ink handling qualities make it an ideal material for bringing life to painting, calligraphy, printmaking and, these days, digital printing. In fact, many paper conservators confrm that this very scientifc method of Hanji making is what has sustained a copy of the Buddhist Dharani Sutra for 1,300 years. Te Pure Light Dharani Sutra, as it is called, is thought to be the oldest copy that is printed in wood block and still preserved to this day. Hanji’s durability has been also ofcially acknowledged by Italy’s Central Institute for Restoration and Conservation of Archival and Library Heritage ICPAL , and Italian conservators have started using Hanji to restore important cultural artifacts, including writing by Saint Francis of Assisi 1182–1226 Troughout the centuries, Hanji has become one of the most versatile materials. In addition to paper’s most conventional application as a writing surface, it has been woven into elements all around us from special occasions to daily lives. During Buddhist ceremonies, for instance, you might encounter ornate temple decorations made with Hanji fowers and lanterns. Still many people use countless household items that are lined inside and out with Hanji, in a manner similar to decoupage. While you may think of paper as a typically fimsy and fragile material, it can be further transformed into independent, three-dimensional structures. Tis is primarily possible only afer being treated with traditional paper craf techniques like jiseung, which converts papers into cords to enable weaving, and joomchi, which binds multiple sheets together like felt. When wallpapers and windows were being redone in the past, old paper was carefully removed so that the scrap sheets could be repurposed into cords or felted paper. Given a new lease on life, the transformed materials could then generate new Hanji objects like baskets, bowls, vases and much more. Many of these Hanji objects are also varnished with natural lacquer or dyes, in order to become water resistant. Paper was even once transformed into protective In the olden days, Hanji used to be called baekji. Tis refers to not only its white hue, but also to the laborious process required to produce it. It’s said the paper required 100 steps to make it – the Korean word for 100 is baek. 옛사람들은 한지를 백지라 불렀다. 흰 빛깔 때문에 백지 白紙 라고도 했지만 백 번의 손질이 필요하다 하여 백지 百紙 라 부르기도 했다. 한지의 정성스럽고 고된 제작 과정을 담고 있는 이름인 것이다. © Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation © Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation © Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation Below Hong Chun-su, a master of Hanji-making, which is designated Korean Intangible Cultural Heritage No.117 Page 6, lef Afer boiling the mulberry wood, Hong removes its bark. Page 6, right Te white inner fbers of the boiled mulberry wood untangle inwater.